Bachtrack, 23.11.2022, Chanda VanderHart

Crumb pilgrimage: mesmerizing Makrokosmos and more at Wien Modern (deutsch: Bezirkszeitung)

Fans of new music in Vienna know that November is a highlight. Wien Modern, founded in 1988 by Claudio Abbado, takes over the city each year on the heels of Halloween, presenting new music throughout the month in an astonishing number of venues and formats. One of the highlights this season is most certainly Georg Crumb’s complete Makrokosmos, housed in an art nouveau theater on Steinhof, towards the outskirts of the city. The performance combines excellent musicianship, experiential packaging and sonically-driven music that makes you feel like your subconscious is being mainlined and your intellect tickled.

Crumb’s four volumes of pieces for amplified piano(s) and percussion ensemble, composed between 1972 and 1979, can be thought of as a pilgrimage of sorts. Crumb wrote Makrokosmos partially as an homage to Béla Bartók’s six-volume Mikrokosmos, and like Bartók’s works, they are designed to run the gamut of piano techniques, but this time with a focus on the contemporary, extended piano, which involves much more than just the 88 keys and a few pedals. Here, players sing, whistle, moan and play slide-whistle into the instrument, tap and use other percussive effects on the soundboard, manipulate overtones, mute the strings and use tumblers, plectrum and thimbles and varied pizzicati techniques. All of this is minutely detailed in the score, which itself contains some of the most well-known examples of graphic notation available and requires extensive deciphering. When done well, they don’t sound like studies, but instead evoke the vastness of the universe, or a dreamscape.

For all these reasons, it is novel to hear all of Makrokosmos performed together... and unheard of in the hands of only two pianists. Alfredo Ovalles and Martyna Zakrzewska were up to the challenge. Ovalles’ ability to differentiate between overlapping soundscapes on a dime is transformative. He moved from the lush, primeval forest of the opening through the sparkling manipulations at the top of the keyboard depicting The Magic Circle of Infinity seamlessly, and the Spiral Galaxy he created to end the first volume was a revelation. Zakrzewska, who performed the more structured and extroverted second volume, brought fire, fingers and flair to the table. She was unstoppable, from the exuberant Morning Music to the crystalline Rain-Death Variations, and navigated the collage of sound worlds in his Litany of the Galactic Bells (including a Hammerklavier quotation) brilliantly. Volume IV, Celestial Mechanics, was a study in collaboration; Ovalles’s deep bass sound complemented Zakrzewska’s energetic explosions spectacularly, and both coordinated brilliantly through the many muted cells and repetitions throughout.

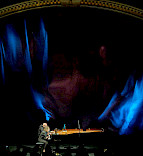

Not relying alone on the theater setting, which itself combines a stark industrial framework with faded Jugendstil flair, the lighting set atmospheric warm tones — golden and red — against crisp blues, and different visual installations were curated for each set. Brigitte Prinzgau and Wolfgang Podgorschek built an otherworldly spool of colorful thread for the first section, held between what looked like large, distended blown glass baubles. It rotated slowly throughout work, the threaded spools changing shape slowly over time. Peter Koger’s installation involved a reflective mirror in the shape of a piano lid, reflecting the inner workings of the instrument outward as well as projected images and interior lighting. Volume IV was framed by an installation simply titled “Schwarz” (black), and backed the musicians with a satiny, billowing curtain, which seemed even darker when the occasional hints of cosmic light peeked through.

If I had a bone to pick it would be Volume III. Because the pianists are joined by a veritable fleet of instruments (played masterfully by percussionists Igor Gross and Emanuel Lipus) which require extensive set-up time, the decision was made to place it in a separate, smaller room. Half the audience was ushered there while the others were herded to the foyer for a drink by astronauts wielding colorful landing sticks, a witty move. Barbis Ruder’s Mundstücke v3 took the front stage, which involved three figures in black who performed various jaw manipulations. Jaws were massaged, distended, held and then a series of elaborate objects were attached to plates inserted within them. These were paraded slowly, like an exotic alien religious ritual. Despite my penchant for a good moonboot, this did put the music in the background, and I am at a loss to how the concept connected to Crumb’s work. That, in combination with my fear of developing permanent tinnitus thanks to more sound in a smaller hall, made me admittedly grumpy.

This should, however, in no way should discourage anyone from grabbing their earplugs and joining in the fun. I cannot imagine a more rewarding way to experience Crumb’s masterpiece in one fell swoop, and recommend it highly to both hard core new music aficionados and the contemporary-music curious who find themselves in Vienna this month.